05 Feb Whats Up – February 2020

Sun and Moon

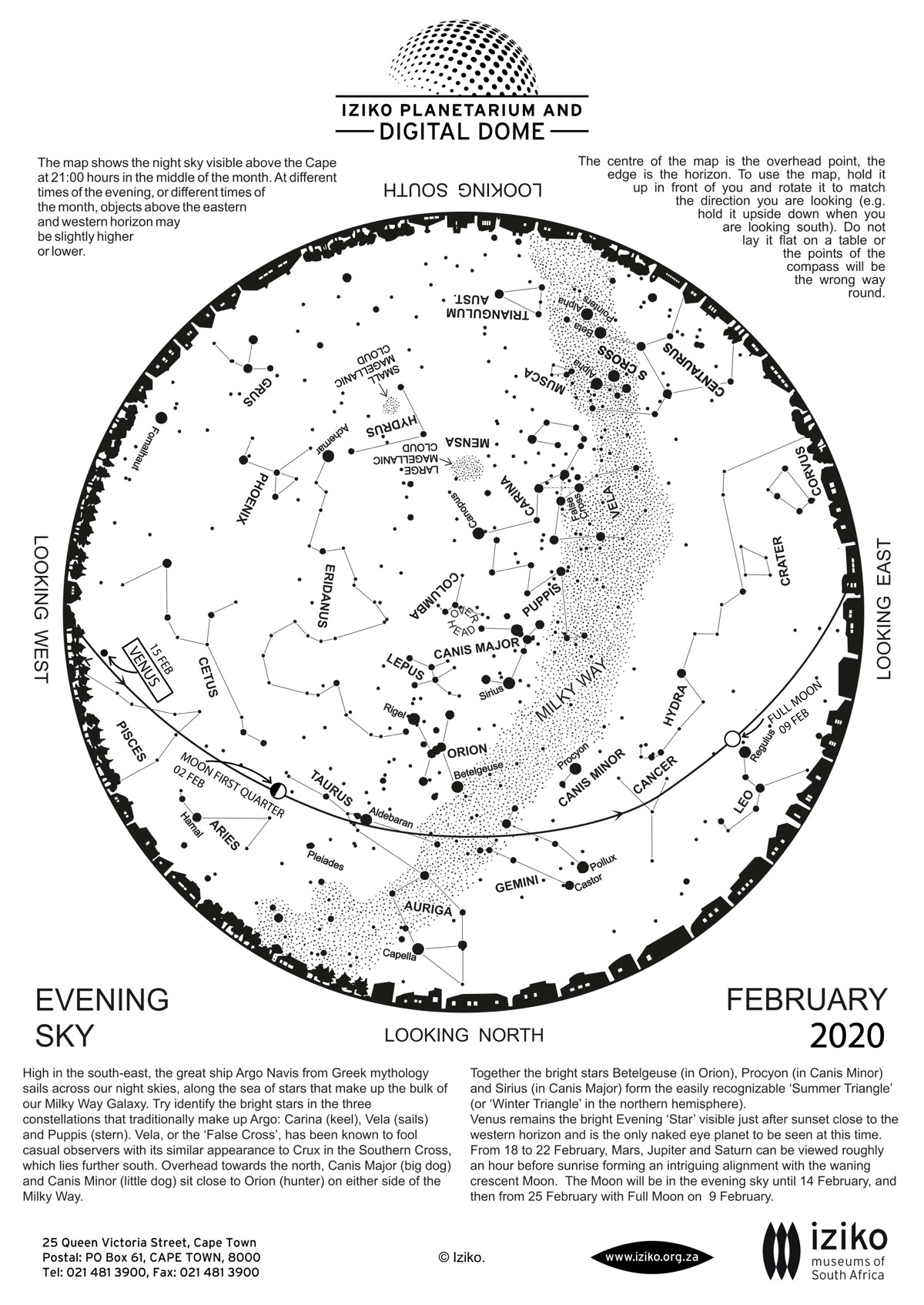

The First Quarter falls on the 1st of February at 03h42. The Full Moon occurs on the 9th of February at 09h33. The Last Quarter Moon falls on the 16th of February at 00h17. The New Moon falls on the 23rd of February at 17h32.

On the 26th of February at 13h35 the Moon will be at apogee (furthest from Earth) at a distance of 406 300 km. The Moon will be at perigee (closest approach to Earth) at a distance of 360 500 km on the 10th of February at 22h30.

Planetary and Other Events – Morning and Evening

Venus can still be observed in the evening sky and shines brightly as the prominent Evening Star. Venus will be near the Moon on the 27th of February. Mars, Jupiter and Saturn can be observed at dawn during this month. Mars will be near the Moon on the 18th of February. Do not miss out on the beautiful and attractive alignment of the crescent Moon, Saturn, Jupiter and Mars on the morning of the 21st of February. Check out how the crescent Moon is positioned between Jupiter and Saturn on the morning sky on the 20th of February.

Two meteor showers are active in February. The gamma-Normids are active from February the 25th to March the 22nd, peaking on the 13th of March. To see the shower, look towards the constellation of Norma between 00:00 AM and 04:00 AM. Around 8 meteors per hour are expected at the peak.

The alpha Centaurids, in the constellation of Centaurus are active from the 28th January to the 21st February, peaking on the 8th of February as the Earth passes through the centre of the meteor stream. Observing prospects for the alpha Centaurids are unfavourable due to the full moon on the 4th. They are best viewed between 22:00 PM and 03:30 AM looking towards the constellation of Centaurus in the South East. Hourly rates are expected to be around 7 meteors per hour at the maximum.

The Evening Sky Stars

The stars of Orion are high in the north on February evenings, with blue-white Rigel above and to the left of the three belt stars, and orange-red Betelgeuse below and to the right of them. Below and to the left of Orion is Aldebaran, brightest star in the Bull, with the Pleiades nearby in the NW at the Bull’s shoulder. The Pleiades, according to the Namaquas, were the daughters of the sky god. When their husband (Aldebaran) shot his arrow (Orion’s sword) at three zebras (Orion’s belt), it fell short. He dared not return home because he had killed no game, and he dared not retrieve his arrow because of the fierce lion (Betelgeuse) which sat watching the zebras. There he sits still, shivering in the cold night and suffering thirst and hunger.

To the right of Orion is Procyon, brightest star in the smaller of Orion’s two hunting dogs. Directly below (N) of Procyon are the stars of the Twins, with the dim stars of Cancer the Crab just to the right. Among the stars of Cancer is what looks to the eye like a fuzzy glow, but which binoculars show to be a cluster of stars, the ‘Beehive’. Directly below Orion is brilliant Capella near the northern horizon, brightest star in the Charioteer. Capella is actually a system of four stars, consisting of a pair of luminous yellow stars and a pair of faint red dwarf stars. Above Orion’s feet (he’s upside down, as you’d expect for a constellation invented in the northern hemisphere) is the Hare, with Orion’s Big Dog above Orion itself and to the right if you’re facing north. The Big Dog boasts the brightest star in the sky, Sirius.

With Sirius nearly overhead, we have Canopus (second brightest star in the sky) high in the south near the Milky Way. Bright Achernar (Senakane, the ‘Little Horn’) is below Canopus and to the right for an observer facing south. The Water Snake and the Small Magellanic Cloud are below Achernar and to the left. Among galaxies separate from our own, the Small Magellanic Cloud is the second nearest, ‘only’ 200 000 light years away. We see it as a dim glow like a detached piece of the Milky Way — and we see it as it was 200 000 years ago. This small satellite galaxy of the Milky Way is gradually being torn apart by the tidal forces it encounters each time it passes near our Milky Way’s largest satellite galaxy, the Large Magellanic Cloud.

This time of year is a great time for snakes in the sky. The Small Cloud lies partly in the southern Water Snake, while the giant monster Water Serpent is visible in the north. Directly to the right of Achernar are the stars of the Phoenix, with the Toucan directly below. The Toucan includes a particularly beautiful cluster of hundreds of thousands of stars, just visible to the naked eye as a dim fuzzy spot if there is no moon and there are no city lights interfering. This cluster, 47 Tucanae, is nearly 120 light years across, and is roughly 20 000 light years away from us. Of the roughly 100 ‘globular clusters’ that orbit the centre of our Milky Way galaxy, 47Tuc is the second brightest.

The Milky Way runs almost due north and south in our skies in early evening this month, from the N into the SSW. The southern portion is very much the brighter, running through the constellations of the Poop Deck, the Compass, the Sails and the Keel (all parts of the ancient constellation of the great ship Argo), with Crux and the Centaur near the horizon.

Rising into eastern evening sky this month are Alphard, the orange star at the heart of Hydra the Water Serpent (lowest in the east at dusk), and Regulus in Leo (low in the northeast).

The Morning Sky Stars

The brilliant Milky Way in the morning sky runs from E to WSW, running from Scutum (the Shield), the Archer and the Scorpion through the Carpenter’s Square, the Altar, the Wolf and the Drawing Compasses, before reaching the Centaur, the Cross and the Housefly, and finally the Great Ship Argo in the west. To the south of the Milky Way are the mostly dim stars of the Peacock, the Bird of Paradise, the Octant, the Chameleon and the Flying Fish.

High in the north, almost overheard, are the stars of Virgo, with blue-white Spica the brightest among them. Spica is actually a double star but unfortunately it is not resolvable with binoculars or a telescope. The two components are less than 32 million kilometres apart (the Sun-Earth distance is 150 million kilometres). The two stars orbit each other every 4 days.

Keeping dangerous bears out of our southern sky is bright orange Arcturus, low in the north and brightest star in the constellation of Boötes, the bear-herd. Arcturus is the brightest star in the sky’s northern hemisphere and the fourth brightest in the sky. Arcturus is cooler and much larger than our sun, radiating more than 200 times as much energy. At 26 times our sun’s diameter, Arcturus would extend a quarter of the way out to the planet Mercury if put in the Sun’s place. Unlike the Sun, it does not derive its energy output from fusing hydrogen to helium in its core, but has reached a stage in its life cycle where it converts helium into carbon.

Sivuyile Manxoyi February 2020

Sivuyile@saao.ac.za