02 May Whats Up – May 2021

In a nutshell…

Moon

| Date | Time | Phase |

|---|---|---|

| 03/05 | 21h50 | Last Quarter |

| 11/05 | 20h59 | New Moon |

| 19/05 | 21h12 | First Quarter |

| 26/05 | 13h13 | Full Moon |

Moon – Earth Relations

Perigee: 357 311 km on the 26/05 at 03h50

Apogee: 406 512 km on the 11/05 at 23h53

Planet Visibility

Mars is visible in the evening sky, near Gemini

Mercury and Venus are visible after sunset, near Taurus

Jupiter is visible in the morning sky, near Aquarius

Saturn is visible in the morning sky, near Capricornus

Meteor Showers

eta Aquarids: active from the 24th of April to the 12th of May (peaking on the 5th of May)

alpha Scorpiids: active from the 11th of April to the 12th of May (peaking on the 3rd of May)

Some easy to identify bright stars

Rigel: blue supergiant in Orion

Betelgeuse: red supergiant in Orion

Procyon: yellowish white star in Canis Minor

Sirius: brightest star in the night sky, located in Canis Major

Antares: red supergiant in Scorpius

Arcturus: red giant in Boötes

Spica: brightest bluish-white star in Virgo

Canopus: yellowish-white star in Carina

Altair: a white star, brightest in Aquila

Regulus: blue–white star and the brightest star in Leo

The Pointers: Alpha and Beta Centauri

Sun and Moon

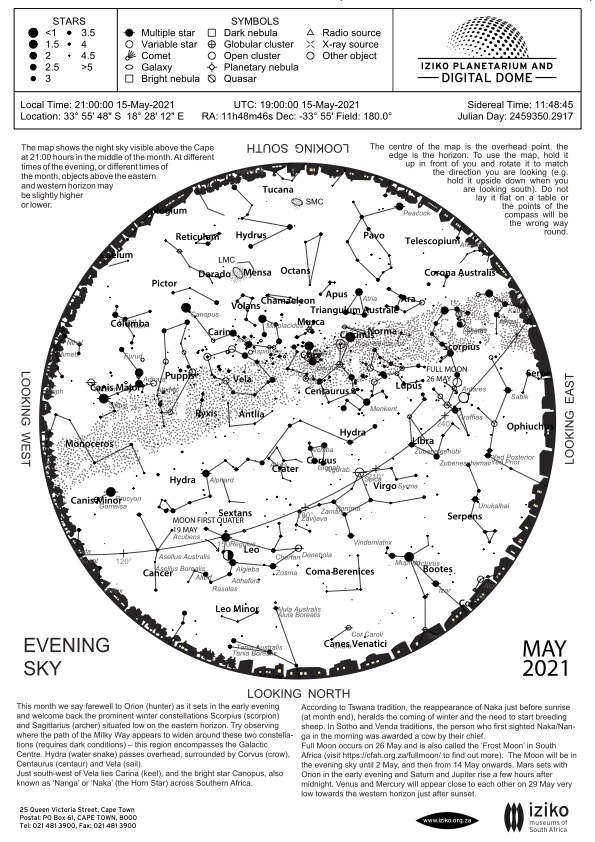

The Last Quarter Moon occurs on the 3rd of May at 21h50. The New Moon falls on the 11th of May at 20h59 and the First Quarter Moon occurs on the 19th of May at 21h12. The Full Moon falls on the 26th of May at 13h13 (this will be a super moon since the moon will be at perigee on the 26th of May, see below).

On the 26th of May at 03h50, the Moon will be at perigee (closest approach to Earth) at a distance of about 357 311 km. The Moon will be at apogee (furthest from the Earth) at a distance of about 406 512km on the 11th of May at 23h53.

There will be a total lunar eclipse on the 26th of May. However, it will not be visible in Africa. It will be seen in Australia and parts of Asia and of North and South America.

Planetary and Other Events – Morning and Evening

Mars, the red planet can still be observed in the evening sky near the stars of the constellation Gemini. Mercury and Venus are located near the stars of the constellation Taurus and can be glimpsed near the horizon on the west in the first week, although this may be challenging due to solar glare. From the second week, the two inner planets may be easily observed just after sunset. Venus and Mercury will be very close to each other on the 28th of May. Jupiter, the biggest planet in our solar system, can be observed in the early morning sky near the stars of the constellation Aquarius. Saturn is still visible in the early morning sky near the stars of the constellation Capricornus. Uranus and Neptune are not visible during this month.

Two meteor showers are active in May. The alpha Scorpiids are active between the 11th of April and the 12th of May, peaking on the 3rd of May. The eta Aquariids are active from the 21st of April to the 12th of May, peaking on the 5th of May.

The alpha Scorpiids are a minor shower with only around 5 meteors per hour expected at their peak. The eta Aquariids meteor shower originates from dust grains ejected by Halley’s Comet. The grains are distributed along the comet’s orbit. Every time the Earth passes through the dust stream, we experience the eta Aquariids meteor shower. To view the eta Aquariids, look towards the constellation Aquarius between 04:00 AM and 05:30 AM. At the peak, around 60 meteors per hour are expected.

The Evening Sky Stars

Orion can still be seen low in the WNW in the early evening, with bright Sirius (‘The Dog Star’) faithfully following at his heels (or possibly chasing Lepus the Hare into the western twilight). Leo’s upside down question mark should be easy to spot in the north, above the few stars in the Great Bear that creep above our horizon. A bit higher in the north is lonely Alphard, the brightest star in the Water Snake, while another and much brighter orange star, Arcturus, rises in the northeast. Arcturus’ atypical motion and chemical composition mark it as a likely ‘immigrant’, a star from a smaller galaxy which long ago was “eaten” by our own Milky Way giant spiral. A bit higher in the sky is blue-white Spica, rising in the ENE in early evening. Spica appears to the naked eye as a single fairly bright star, but it is actually a system of 5 stars 260 light years away. The two brightest stars in the Spica system rotate around each other once every 4 days, and are respectively 13 400 and 1 700 times as bright as our own Sun. Paradoxically, most of the stars you can see without a telescope are brighter than our Sun, even though most stars in our neighbourhood are much dimmer than the Sun. This is because we can see bright stars even when they are far away, while most stars would be too dim to spot even at the distance of our closest stellar neighbours.

Gliese 581, host star to two very interesting planets, is a typical example. This first of these two planets is about 5-6 times the Earth’s mass and is located in the “habitable zone”, where it is possible for liquid water oceans to exist on the planet’s surface. The second of these is smaller, with a mass about twice that of Earth, but closer to its parent star than the first. At only 20 light years away, Gliese 581 is one of our near neighbours, but it is 66 times too faint to see with the unaided eye.

Rising in the southeast are the stars of the Scorpion and the Wolf, with the stars of the Cross and the Pointers high in the SE. Look out for Antares, the bright red star in Scorpius. Well up in the SSW is Canopus, second brightest star in the sky and brightest in the great ship Argo, serenely sailing along the Milky Way, which runs from Scorpio in the SE to the Twins and the Unicorn in the NW. Accompanying the Argo are the Flying Fish and the Swordfish, with the Fly and the Bird of Paradise flying on ahead.

The Morning Sky Stars

Achernar, the “Little Horn”, shines brightly high in the SE before dawn, with the celestial river Eridanus flowing down toward the east. Assortments of birds occupy much of the southern sky, including (from west to east) the Bird of Paradise, the Peacock, the Crane, the Toucan and the Phoenix. The stars of the Pointers and the Cross are now low in the SW, with the Scorpion, the Wolf and the Altar in the WSW and Sagittarius the Archer still halfway up in the west. The centre of our galaxy, with its most brilliant parts, is well into the west before dawn, but the Great Rift (a dark band running through the northern Milky Way) is still easy to see. The brightest stars in the NW are Altair in the Eagle, Vega, very low in the NW in the Lyre, and Deneb, the tail of the Swan. The Swan, at the far northern end of our Milky Way on May mornings before dawn, is also known as the Northern Cross. The dim star at the southern end of the Northern Cross is Albireo, a beautiful gold-and-blue double star when viewed through a telescope. Albireo’s two suns are far brighter than ours, but they would still be dim compared to Deneb. We don’t know the exact distance to Deneb, and can’t be sure just how bright it is, but the minimum estimate is 60 000 times the brightness of the Sun!

Just east of the point overhead is Fomalhaut, brightest star in the Southern Fish, with the dimmer stars of the Sea Goat and the Water Carrier just to the north. Low in the northeast are the stars of the Great Square of Pegasus, with the two fishes to the south and east, tied together by their tails. Rising in the E before dawn are the stars of the Whale.

But the most carefully watched star on May mornings in at least some parts of Southern Africa was Canopus, known to some as ‘Naka’ (the Horn). It was believed among the Sotho that the first person to see the star would be very prosperous that year, with a rich harvest and good luck to the end of their life. In olden times the chief would give the lucky person a heifer. Young Sotho men would camp on hilltops where they made fires and watched the early morning skies in the South. The first one to see Canopus would blow a sable antelope ceremonial horn (phalafala), signalling to the villagers that it was time to send the boys for initiation. The day after Naka was sighted was the time for the men with divining bones to examine their bones in still water, to predict the tribe’s luck for the coming year. Among the Mapela, the first man to see the star would begin ululating loudly enough to be heard in the next village, which would then join the noise making to inform other villages, each in turn until all knew Canopus had been seen. For the isiXhosa speaking people, the sighting of Canopus, called uCanzibe, signaled the beginning of the season for the celebration of the last days of boyhood by boys intending to go to the initiation school to become men.

Sivuyile Manxoyi

sivuyile@saao.ac.za

The evening sky over Cape Town

The evening sky over Johannesburg